“I am always translating, he thinks: if not language to language, then person to person.”

The rise of the polyglot

Cromwell’s talent for languages was one of the first things that struck me during Simon Haisell's slow read of Wolf Hall - even as a boy, he is able to surprise his brother-in-law Morgan Williams by thanking him in Welsh as he takes his leave, a skill he’s picked up simply by “hanging around the Williamses’ households”. By the time he is summoned from the Frescobaldi kitchen in Florence to take his new place as a clerk in the counting house, he’s added a few more tongues on his travels:

“His thoughts bubbled and swirled, Tuscan, Putney, Castilian oaths. But when he committed his thoughts to paper they came out in Latin and perfectly smooth.”

After returning to England, these language skills are a key part of his usefulness to Cardinal Wolsey, both in facilitating international business and in court intrigues closer to home. After Wolsey’s fall, Cromwell remembers his instructions on commissioning fine mirrors from Venice:

“Now, Thomas, you will add to your letter some Venetian endearments, some covert phrases that will suggest, in the local dialect and the most delicate way possible, that I pay top rates.”

Sometimes even Cromwell’s linguistic abilities have their limits though, as he ruefully concludes after Wolsey’s meeting with Sir Thomas Boleyn:

“The trouble with England, he thinks, is that it’s so poor in gesture. We shall have to develop a hand signal for ‘Back off, our prince is fucking this man’s daughter.’ He is surprised that the Italians have not done it. Though perhaps they have, and he just never caught on.”

An ear for languages

Wolsey also hopes that Cromwell’s knowledge of Spanish might help him discover “what Queen Catalina will say, in private and unleashed, when she has slipped the noose of the diplomatic Latin in which it will be broken to her that the king - after they have spent twenty years together - would like to marry another lady.” Cromwell is able to use his language skills to pick up information throughout the story, such as listening in on Mark Smeaton’s (Flemish) gossip about Anne Boleyn and Tom Wyatt.

He’s not the only one playing this game - the ambassador Chapuys is described as collecting gossip from various sources in French, Italian, and “God knows what - Latin?” as Cromwell ponders whether he is being allowed to hear the ambassador’s bodyguards chattering about him in Flemish deliberately as “some elaborate double-bluff”. Jane Seymour isn’t so well-equipped, and asks Cromwell to try to speak more English with Anne Boleyn to make their conversations easier for her to follow.

As shown by his shift from multi-lingual cursing to smooth written Latin, Cromwell’s skill isn’t just in the languages he speaks, but the way he speaks them. His consciousness of this code-switching, and its usefulness, can be seen when he compares the experience of exchanging “a few tags of Greek” with Cranmer & Wriothesley to slipping back into the “blasphemous and rapid” slang of his childhood to discover “Putney’s opinion of the fucken Bullens” from the boatman he knew as a child.

Why bother learning English?

The point at which I really started paying attention to the languages spoken in Wolf Hall was the dinner party hosted by Italian merchant Antonio Bonvisi in 1530, at which Cromwell, More, and Chapuys are all present, and English, French, Latin and Italian are spoken.

What stood out to me was the fact that it appears totally natural that the Emperor’s ambassador speaks no English: “like any other diplomat, he will never take the trouble to learn English, for how will that help him in his next posting?” This was a real eye-opener for me, having grown up as an English-speaker in a world where English is a global lingua franca. (What is the most spoken language? | Ethnologue Free)

In Henry VIII’s time, the language of this little island nation was of limited use, and French would have played the main role in European courtly life. When the host announces that they will switch to French, the guests do so seamlessly - and go further when Chapuys attempts discretion by dropping into Latin, but “the company, linguistically agile, sit and smile at him”. It is noted that More, the scholar, can also speak Greek, whereas Cromwell, with his more human touch, has “naturally slid back into Italian” at the end of the evening to continue trading gossip with his host.

The elaborate dance of picking a language before starting a conversation recurs with Catherine (who insists in speaking English to highlight her claim as Queen of England) and Anne (who prefers to speak French). This made me oddly nostalgic for my time living in Luxembourg, where establishing the speakers’ strongest common language was often a necessary first step before making conversational progress.

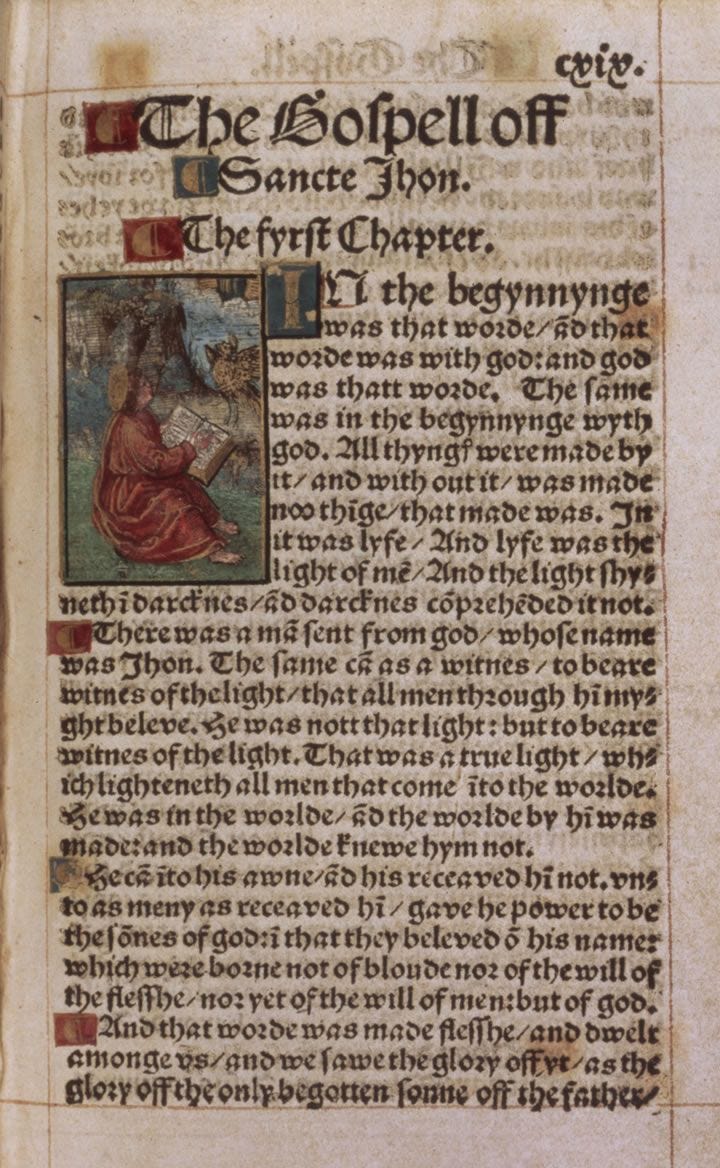

The Bible in translation

Cromwell read the Bible in English before it was cool. That is to say, he was a committed (if discreet) gospeller at a time when that came with a very real risk of being burned alive like James Bainham.

“Tyndale says, now abideth faith, hope and love, even these three; but the greatest of these is love. Thomas More thinks it is a wicked mistranslation. He insists on ‘charity’. He would chain you up, for a mistranslation. He would, for a difference in your Greek, kill you.”

Anne Boleyn is also a Bible-reader, having perhaps learned her scriptures in France where “King François allows the Bible in French”. I loved the subtle pyschology of a passage where, after remembering his traumatic childhood experience at the burning of the Lollard Joan Boughton, Cromwell starts speaking in French (“he does not know why”) and thinking of his fellow gospeller Anne calling to him (“Maître Cremuel, à moi”).

When I started noticing the languages of Wolf Hall, it was mostly just as an impressive and ever-growing list (Welsh, Castilian, Flemish, French, Latin, Greek…), but the further I read, the more I realised that the theme of language and translation went deeper and was more connected to the transformations that were taking place in Cromwell’s lifetime, often with him pushing them on. Martin, the Tower gaoler, “learned to read on Wycliffe’s gospel, which his father hid in their roof under the thatch. This is a new England, an England where Martin can dust the old text down, and show it to his neighbours.” By the end of Wolf Hall, Cromwell has a new English Bible almost ready, and is hopeful of persuading Henry to accept it by including a flattering image of him “displayed in glory, head of the church” on the title page.

Treasonous language (and the power of the printing press)

The spread of translated Bibles is of course linked to the rise of the printing press and the possibility of bulk printing. This raises a new problem for Cromwell, as he notes when considering the case of Elizabeth Barton’s prophecies against Henry:

“He can see that, in the years ahead, treason will take new and various forms. When the last treason act was made, no one could circulate their words in a printed book or bill, because printed books were not thought of. He feels a moment of jealousy towards the dead, to those who served kings in slower times than these; nowadays the products of some bought or poisoned brain can be disseminated through Europe in a month.”

Cromwell does subsequently introduce legislation drawing on and ‘clarifying’ old precedents in order to establish a new form of treason, but remains acutely aware of the power of this new type of propaganda, for example in his struggle with More:

“‘I suppose he’s writing an account of today,’ he says. ‘And sending it out of the kingdom to be printed. Depend upon it, in the eyes of Europe we will be the fools and the oppressors, and he will be the poor victim with the better turn of phrase.’”

The language of the gutter

In honour of Cromwell’s ability to swear in Tuscan, Putney, and Castilian, I couldn’t resist a quick compilation of some striking moments of Tudor profanity from Wolf Hall:

Walter Cromwell, making a strong start in the first scene: “By the blood of creeping Christ, stand on your feet.”

The Duke of Norfolk, panicky and impatient during the crisis over Harry Percy’s claim to be married to Anne Boleyn: “Oh, by the thrice-beshitten shroud of Lazarus!”

Charles Brandon, wondering how Cromwell came to be so powerful: “We ask ourselves, but by the steaming blood of Christ we have no bloody answer.”

Cristophe’s “gutter French” outburst on waking: “Oh by the hairy balls of Jesus.”

Sometimes, however, it is wiser not to acknowledge foreign profanities. When planning the royal trip to Calais, Cromwell considers the possibility that the people of Calais might line up to shout “Putain!” at Anne, but concludes: “If they sing obscene songs, we will simply refuse to understand them.”

Other-worldly languages

Perhaps I should end on a more elevated note. As part of our slow read, I have been enjoying Simon’s posts on the haunting of Wolf Hall, highlighting the ways that Mantel’s narrative goes beyond the everyday. Her writing on languages is no exception - here are a few examples:

“He wonders again if the dead need translators; perhaps in a moment, in a simple twist of unbecoming, they know everything they need to know.”

Henry’s statement that he will back Cromwell’s efforts to unlock the church’s wealth is “like hearing a perfect line of poetry, in a language you knew before you were born.”

“When you are writing laws, you are testing words to find their utmost power. Like spells, they have to make things happen in the real world, and like spells, they only work if people believe in them.”

I spotted a lot of language references when I wrote this, but have since discovered that I missed the devastating impact of Cromwell’s curiosity about the Polish language. On the day that his wife Liz died:

"He would have been home early, if he had not arranged to meet up in the German enclave, the Steelyard, with a man from Rostock, who brought along a man from Stettin, who offered to teach him some Polish. It's worse than Welsh, he says at the end of the evening. I'll need a lot of practice."

When his mother-in-law asks where he was, this even adds a flash of dark humour amidst the tragedy:

"And later? Later I was learning Polish. Of course. You would be, she says."

Thank you so much for the Tudor profanity. There are a few I plan to work into a conversation ASAP. Great post. Very well done!